I have vague memories from school of a chap called Milton writing a poem called Paradise Lost.

Well, this is not that Milton. Nor is this that paradise. And this sure ain’t no poem. This is Giles Milton telling the story of the ‘lost paradise’ of Smyrna (Izmir today). Here, watch some of it for yourself, with this 103 seconds of original footage of ‘the catastrophe’…

So, what happened?

I am so glad you asked that question.

I’ve been dying to tell you.

The story goes something like this…

The Greek presence in Smyrna goes back 3000 years. When the Treaty of Versailles divided the spoils after World War I, Smyrna was given to Greece. By 1922, the “Greek population (in Smyrna) was at least twice that of Athens” (4). In addition to this, “Smyrna had an impeccable Christian pedigree” (4). It was one of the seven churches in Revelation in the 1st century and its bishop (Polycarp) was martyred early in the 2nd century. So it is no great surprise that during the 600 year Ottoman Empire, the Turks referred to Smyrna as Gâvur İzmir (Infidel Smyrna)—”a majority Christian city in a resolutely Muslim world” (14). But it gets even more intriguing. The city had gathered these fabulously wealthy European families (Levantines), around whom Milton tells his story of this cosmopolitan, tolerant city.

In no city in the world did East and West mingle physically in so spectacular a manner (9).

It was quite the place! There is this extraordinary photo of the people of Smyrna filling an opera house in 1917, apparently oblivious to the fact that some of the darkest days of the war were going on just a few hundred miles away. Then in 1922, in the space of a few days, even a few hours, hundreds of years of history fell apart. Smyrna burns to the ground.

With Türkiye being one of the easier countries for which to gain a visa today, my work takes me there for meetings every now and then. On my first visit to Izmir in 2015, all I was interested in—and the only thing I knew about—was the Polycarp church. After a visit in 2023, I purchased Milton’s book and was captivated—and yes, even a bit traumatised—by the story. I promised myself that if I ever returned, I’d keep an afternoon free to wander around the sites.

And so it came to pass, earlier this month. I contacted a friendly travel agent, only to receive the news that, given the tension that is still in the air between the Greeks and the Turks, there is no guided tourist-trail to follow with this particular slice of history. But then I remembered that there was a family friend, with a shared Indian upbringing, in the area and they agreed to walk me around the city.

The Green Blob

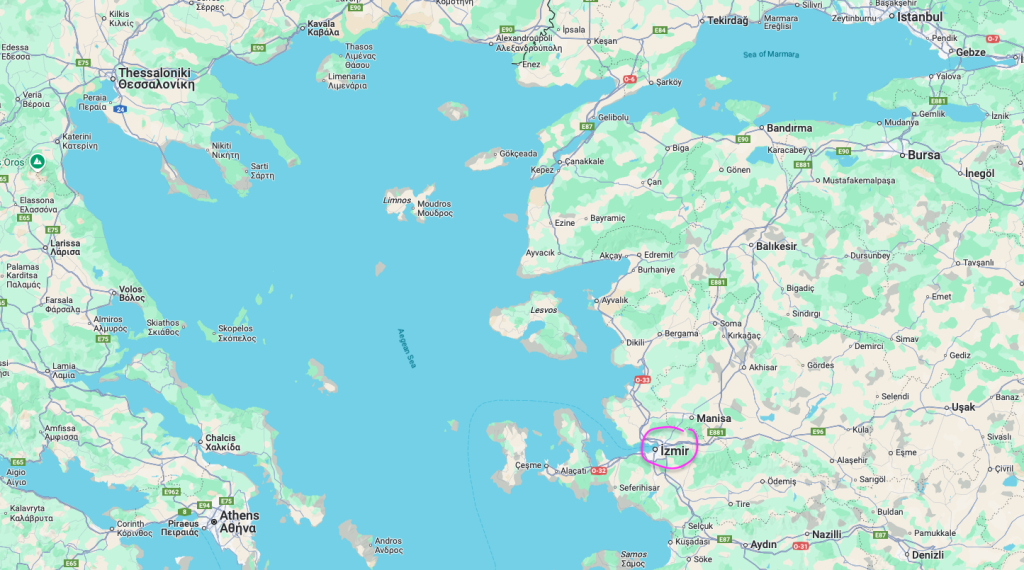

So, on a Thursday afternoon, I travelled from the airport hotel into the Alsancak train station. We grabbed some local street food from an adjacent building and then walked across to the green blob on the map (see below): Kültürpark İzmir. It is a tree-filled park with an impressive walking track around its perimeter, from which we saw evidence of the space being used as a fairground.

Now, we need to pause for some history to appreciate the significance of this blob.

In 1919 Greek troops entered Smyrna to take what was now theirs. Filled with dreams of a new Greek Empire and backed by the Allies, especially the British PM, Lloyd George, they headed for the interior. “The Greek army swept all before it” (208). It was cruel and brutal. However, they overreached, going well beyond the point that their supply lines could sustain. The succession of victories were soon replaced by a string of defeats as they limped their way back to the Smyrna coastline. Eventually, it was a rabble of a Greek army that dribbles into Smyrna, along with Greek communities they picked up along the way.

But there was another force at work. Further east, a young Mustafa Kemal—soon to become Atatürk, the father of modern Türkiye—had assembled an army of nationalists. He waited for his moment—and then he pressed forward. It became a story of both ‘retreating Greeks’ and ‘advancing Turks’.

Atatürk arrived in Smyrna just a few days after the Greeks. While historians on both sides continue to debate who actually started the fire, there are trustworthy eye-witness accounts of unruly edges of the Turkish army looting and setting fire to the Greek and Armenian Quarters (ie the so-called ‘Christian’ part of the city). Soon “Mustafa Kemal’s army—which had entered the city with such discipline—was completely out of control” (295).

‘I saw with my own eyes the Turks taking bombs, gunpowder, kerosene and everything necessary to start fires, in wagonfulls here and there in the streets’ (287).

To this day, most Turkish historians persist in claiming that the fire … was an act of sabotage on the part of the Greeks and Armenians. Yet there are scores of impartial accounts that testify to the fact that the Turkish army deliberately set fire to Smyrna (307).

And remember, these are probably the same historians who deny that the Armenian genocide happened seven years earlier! Actually, the last remaining Armenians lived in this cosmopolitan, infidel-city of Smyrna—but not for long…

Now, back to the green blob on that map. Any guesses with its significance?

It covers those old Greek and Armenian Quarters. These two communities were burnt to the ground and were never rebuilt. It was ‘Turkey for the Turks’, and this was something of a purifying fire, ridding the city of every vestige of the Greeks. Believe it or not, a change in wind direction at just the wrong time spread the fire even more ferociously.

The Statue

After walking much of the circumference of the green blob, we headed for the waterfront, retracing the steps of some of the tens of thousands who did so across those few days in September 1922. However, before we reached the quay, we were greeted by this huge memorial to Atatürk astride his horse, in what is a flag-rimmed patriotic space.

Atatürk’s arm is outstretched and his finger is pointing to the ocean sea (Oops, I’ve discovered that people in this part of the world are sensitive about their ‘sea’ being called an ‘ocean’!). Anyhow, the words on the memorial say something about ‘throwing the Greeks into the Aegean (Sea)’. Again, this is a disputed point, with many historians asserting that most of the Greek army had already been evacuated on warships in the days before Atatürk’s arrival. It was mostly the everyday Greeks and Armenians, from the city and from further inland, who were caught in this push to the sea.

[After I posted this blog, I realised that my earlier Polycarp post had this aerial photo which captures this area of the city so well. You can see the green blob and the green strip so clearly, with the statue in the space between the end of the strip and the famous (Konak) pier jutting out into the ocean sea…]

The Green Strip

Less than one hundred metres from the statue is the start of the waterfront that you see on-fire in the film. With so much reclaimed land now, depicted by the green strip just to the west of the green blob on the map, the narrowness of that space in 1922 is lost on us a bit. It was about the ‘width of a football field’.

The Smyrna quayside had indeed become a scene of abject human misery. Almost two miles long … it was large enough to accommodate hundreds of thousands of homeless people. The transformation into a makeshift refugee camp had been rapid and dramatic. Just a few days earlier the waterfront had been alive to the sound of gypsy orchestras and brass bands. Now, the gaiety had been replaced by rank squalor. The same people who had only recently spent their evenings sauntering up and down in their evening finery were now camped out in the open air with neither privacy nor provisions…

By the time dusk fell on that terrible Wednesday, the quayside was crowded with almost half a million refugees. They stood in real danger of being burned alive for the fire had by now reached the waterfront—a scalding pulsating heat that was transmitted from building to building …

… (in the words of a tourist, Oran Raber): ‘The screams of the frantic mob on the quay could easily be heard a mile distant. There was a choice of three kinds of death: the fire behind, the Turks waiting at the side streets, and the ocean in front … in modern chronicles, there has probably been nothing to compare with the night of September 13 in Smyrna’ (318-19).

Meanwhile—or should I say ‘all the while’—there were 21 Allied warships watching unmoved from the bay. Yes, that’s right. Twenty-one. It is from the deck of one of them that we have that footage of the fire! They had been there from the beginning, giving some assurance of protection. But the protection never came. Why? These Western powers, floating like seaborn vultures, adopted a neutrality as they read the situation. Atatürk was in the ascendency. They dare not be seen to aid the refugees as they positioned themselves to be mates with Atatürk and the nation to be formed out of the crumbling Ottoman Empire. Like many before them, and after them, their eyes were on the oil. Eventually, far too late,

One by one, each of the great battleships in the bay of Smyrna was loaded with a cargo of terrified humanity … Yet the sailors and officers knew that there was a grim arithmetic to the situation in which they found themselves. There were some half a million people on the quayside but there was space on board the battleships for less than one tenth of that number (324, 327).

Incredibly, “they never returned for more” (355). It was ‘one and done’. They loaded up once and never returned for a second load…

… and then there was Asa

He returned. Oh yes, he did. Again and again.

Let’s call him who he was. Not just an American, or a humanitarian. Nah. Nah. He was a missionary, with the call of Jesus on his life—running YMCA youth camps in Smyrna. By all accounts he was an odd and unimpressive man. “When he smiled, he looked like a frog” (352). Others described him as squat and wimpy, “tiny of stature” (356), with curvature of the spine‚ and never having achieved much with his life.

However when faced with this Allied ‘paralysis of neutrality’, it was a case of ‘not on my watch’. He establishes an aid organisation, comprising just himself. With some bluff, possibly a little bribery, and a whole lot of bravery and brilliance he manages to coerce the Greek government into appointing him “as admiral of the Greek navy, with all control over Greek ships” (359). “Hitherto all I knew about ships is how to be sick in them” (359). Then he proceeds to pluck tens of thousands of people from the quayside, transporting them to nearby Greek islands. Given that the Turks were deporting all the men they could to inland camps, and likely death—most of those being rescued were women and children.

He is a one-man Dunkirk.

(Asa) Jennings was soon to … lead what must rank as the most extraordinary rescue operation in the entire twentieth century (352).

Now that is a big call. But when you read the story, it is hard to dispute it. And I am left asking, “Where is the movie?”

nice chatting

Paul

PS: I tend to get lost in the tributaries of these kinds of stories, enabled by YouTube distractions and Wikipedia trails. Here are a few…

(a) A 56-second trailer for a documentary on Smyrna. It shows the narrow space at the waterfront.

(b) A longer piece of the original footage.

(c) A bit more of the Asa Jennings story.

(d) Dr Esther Lovejoy is mentioned in Milton’s story, working with Asa Jennings in the rescue operation. She pioneered the work which later became known as Doctors Without Borders. Here is the full text of her book, Certain Samaritans, which includes her eye-witness account of the Smyrna Catastrophe. I also found a recent lecture online which tells more of her story.

About Me

the art of unpacking

After a childhood in India, a theological training in the USA and a pastoral ministry in Southland (New Zealand), I spent twenty years in theological education in New Zealand — first at Laidlaw College and then at Carey Baptist College, where I served as principal. In 2009 I began working with Langham Partnership and since 2013 I have been the Programme Director (Langham Preaching). Through it all I've cherished the experience of the 'gracious hand of God upon me' and I've relished the opportunity to 'unpack', or exegete, all that I encounter in my walk through life with Jesus.

Recent Posts

Football helps me train preachers. See, when you speak to me about football—or, ‘footie’—I need to know where your feet are before I can understand what you mean. Are your feet in Ireland, or Brazil, or the USA, or NZ—or in crazy Australia? It must be the most fanatical sporting nation in the world. Within…

Having been born in 1959, I don’t remember much about the 1960s. But I have heard a lot. Hippies. Drugs. Rock ‘n Roll. Assassinations. Moon-walking. A quick trip across to ChatGPT informs me immediately that it was ‘a transformative decade across the world’—marked by the civil rights and feminist movements, Cold War tensions, consumerism and…

Amazing! This is a piece of history and a heroic story I had never heard about before. Someone should make a movie about Asa Jennings!

You’ll need to visit with Raewyn one day 🙂

I’d love to see a movie on Asa Jennings as well … with a focus on the collaborative work with Esther Lovejoy as well.

Trust you are doing well.