Having been born in 1959, I don’t remember much about the 1960s. But I have heard a lot. Hippies. Drugs. Rock ‘n Roll. Assassinations. Moon-walking. A quick trip across to ChatGPT informs me immediately that it was ‘a transformative decade across the world’—marked by the civil rights and feminist movements, Cold War tensions, consumerism and a rising, rebellious, countercultural baby-boomer generation.

Meanwhile, across in Egypt, the ancient church founded by Gospel-writer St Mark himself was undergoing a reformation under the leadership of “a silent patriarch”, Pope Kyrillos VI. Enthroned in 1959, he led the Coptic Orthodox Church through ‘a transformative decade’, before dying—or, ‘reposing’, as this author keeps expressing it—in 1971.

Listen to these words from the opening page of Daniel Fanous’ book:

Kyrillos inherited a broken, weeping and profusely bleeding Church from his abducted and exiled predecessor. Yes, just twelve short years later, Kyrillos stood at the head of a nearly impossible spiritual revolution. What began in a cave deep within the desert continued in a small and unassuming house in Old Cairo and ended in the transformation of an entire Church. It is, to my knowledge, one of the most profound, beautiful, pervasive, and overwhelmingly spiritual revolutions in the history of Christianity since the Apostolic Age (11-12).

Goodness me. “How come I’d never heard of him…? If this is true—count me in, all in.”

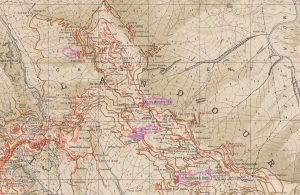

Father Daniel is intent on saving Kyrillos VI—also known as Cyril VI—from becoming merely ‘an icon on the wall,’ as he expresses it in dedicating the book to his children. He does a great job. It is an extraordinary story, in a 400 page brick of a book that I carried in my hand luggage all around the world in June/July. It started back in November when our transit in Cairo was extended, unexpectedly, by a couple of days. My Langham colleague, Maggy, and her husband, Beshara (a devoted, lifelong member of the Coptic Orthodox Church), took us to visit three Coptic monasteries in Wadi Al-Natrun.

From one of them, we walked out to this cave. It was just a place and a name to me at the time—but now I wish I had taken a photo standing there [NB: this is Barby’s photo]. We both remember a Coptic leader from Canada being there as well and how he looked intently into my face and said, “You need to read the book about this man”.

And so it came to pass, with Beshara’s help.

I read through all those pages, as I traveled across all those time zones, with that Coptic Canadian’s comment ever with me. Now I ask myself, “Why did he stress the importance of this man’s life to a total stranger?” I have come up with a few answers…

it is the consecration

At age 4, little Azer (Kyrillos’ name as a child) was mesmerised by the visit of a monk to their home. When he fell asleep on the monk’s lap, his mum was so embarrassed. The monk’s response? “Let him sleep here because he is from our stock. He is one of us” (24). During one school holiday a Muslim sheikh saw Azer’s “unusual fascination with the Scriptures” (25) and so helped him learn how to memorise long texts, starting with the Gospel of John. By the end of the holidays both the lad—and the sheikh—had memorised the entire Gospel together.

Before his mum died (with Azer at 10 years of age), she passed on to him a love for the saints. During the year, in their home, they would journey from one feast day, in memory of a saint, to the next feast day. Each year they would leave the home and go on these pilgrimages. They’d walk 5+ hours for the weeklong celebrations of a relatively unknown monk, Menas—martyred early in the 4th century. A bit reminiscent of Jesus in the temple, while everyone else was partying, Azer remained in the church, fascinated by Menas—“as a most unusual relationship proceeds that touches every fabric of his history and existence” (28).

Menas becomes his patron saint and when he becomes a monk, he takes his name—becoming known as Father Mina. Later he builds a church in Cairo with the Menas name, the first one to bear that name in one thousand years. As it happens, in 2016, Barby and I visited that church—although Beshara tells me it is a different building today. It is where I took my most favourite photo from all these years of working with Langham.

And so from these early years, Azer’s life was set on a trajectory of an unusual consecration—“the path of living singularly, purposefully and absolutely for God—a path of hiddenness, stillness, smallness, of being unknown to all but God” (17).

it is the solitude

All Azer ever wanted to be was a monk, having this lifelong encounter with God in prayer, liturgy and silence. Even as a boy, he was “living a monastic life within his own bedroom, (with) his family looking on bewildered, somewhere between inspired and disturbed” (41). So, eventually, it is off to the monastery that he goes—“the home of his enduring hopes” (56).

It is here that he comes under the influence of Isaac the Syrian, who sits alongside Menas as the biggest influences on his life. Isaac wrote the Ascetic Homilies—and Father Mina wrote it out, transcribing it four times. “Each reading, transcription and memorisation was a vigorous, determined and consummate immersion in the thought-world of the Syrian” (69). It is uncanny how Father Mina’s life so closely followed Isaac’s—and right at the core is the pursuit of solitude. “Why?”, we may ask.

Solitude beckoned the love of God into his soul, overflowing … upon all humanity (106).

It was a difficult biography to write, given that Father Mina never kept a diary—and he rarely preached. In fact, later on, “as patriarch, Kyrillos never delivered a homily” (231). However there is the occasional article attributed to him. Listen to him write about prayer:

(Prayer) is nourishment for our souls, light to our minds, filling for our days, proof of our hope, our grace, the treasure of monks, and the repository of the silent in serenity … It is the mother of virtues and every religious instinct, the hedgerow of every virtue and its protector. It is the store of graces, the metal of blessings, guard of satisfaction, controller of anger, and the calming of the haughty spirit … (134).

At one point in the monastery—when talk of putting him on a pathway to becoming a bishop was in the air—he just got up and left. “Mina’s intention could hardly be mistaken: he sought to disappear permanently” (87). Eventually he was coaxed back to the monastery, but not for long. He negotiated to live his life in that cave, returning to the monastery only for liturgy on Sunday. But here’s the thing. Life in the cave was not some quiet bliss. “Each day was lived in piercing and tortuous affliction” (95). It is a bit reminiscent of Jesus being tested in the wilderness. But when he returned each Sunday, “his face radiated with solace and quiet satisfaction” (96).

Although he emerged from the three years in the cave “mentally and physically emaciated … the grace of God had lighted upon him” (98, 99)—and everything changed. He returned to the monastery. However he became insubordinate to the authorities when seven elderly monks were mistreated. In solidarity, he chose to accompany them in exile in Cairo. Here he lived alone in a crumbling, abandoned Napoleonic-era windmill.

The life of solitude continued. He never really left the desert, as he continued with “an internalised desert” (233). He was to become “the patriarch (who) remained a monk” (227)—a silent patriarch.

it is the healing

I was going to skip this one…

But it is hard to overlook the fact that in 2013, “eighteen volumes of miracle accounts emerged” (12) from the encounters which people had with Kyrillos. Did you get that? Eighteen volumes. Astonishing. It is a bit reminiscent of Jesus. “No other period in the history of the Coptic Church witnesses so many reports of unfamiliar and extraordinary events” (130)—starting in the 1930s when so much of the world was so dark.

For me, the most stunning story in the book is how the Muslim President (Nasser) and the Coptic Patriarch (Kyrillos) become friends. The turning point is when Nasser’s daughter is healed through Kyrillos’ simple, bold prayer and anointing with oil. Seriously, get hold of the book and read pp279-289…! As I have tended to do over the years with such purple patches, I read much of it aloud to Barby. After years of tension, Nasser’s attitude towards the Coptic Orthodox Church changed overnight—yes, literally, over one night.

it is the discipleship

In much of the early decades of the twentieth century, the Coptic Church was in decline: “Once we were a head, we have now become a tail … our lambs have run away” (160).

Enter Habib Girgis. He believed that reform could only come from within the church. So what did he do? Where did he start? He developed “a simple and modest catechism, otherwise known as Sunday School” (161). What became known as the Sunday School Movement (SSM) was born. It was guided by two principles: education of the young and discipleship. By 1938, there were 85 branches of the SSM in Cairo alone. In what is a curious approach for many Western Christians today, “We wanted to study the old Church in order to revive the modern Church” (162).

And guess who became the key leader in this movement?

Father Mina, now living in St Menas’ Monastery in Old Cairo.

In that unassuming church, Fr Mina modeled a rare and radical monastic ideal, an ascetic lifestyle that was just as radically open to the intellectual aspirations of the present age … He had found a place for fervent youth, ‘for whom there was no place yet in the existing monasteries’, carving out a ‘harbour of salvation’ in a Church that at the time saw no need for them and had not the faintest desire to accommodate them. At no point, it must be said, did the quiet recluse actively seek out candidates for the consecrated life; rather, these young men came to him (174)

… In a matter of only a few years St Menas in Old Cairo, through Fr Mina, had inspired the Sunday School Movement to enter the clerical ranks. Here at St Menas’, a host of lay servants, priests, monks, abbots, bishops, metropolitans and two patriarchs, no less, were to be found. The seeds once planted by Habib Girgis, and now nourished, directed and empowered by Fr Mina would literally, in the space of a decade, take Egypt by storm (175).

‘Take Egypt by storm’. Amazing, eh?

Good ol-fashioned, deep and catechetical, discipleship. A bit reminiscent of Jesus, isn’t it?

The words ‘Sunday School’ hardly capture the resolve, tenacity and almost fanatical intrepidity of this deeply counter-cultural movement (162) … Few could have suspected the influence of a mostly silent recluse and his handful of restless disciples (351).

And as we shall see, when Fr Mina eventually becomes patriarch, just guess where he turns to find new leadership for the spiritual revolution that was needed?

At play in the qauint Monastery of St Menas in Old Cairo was a revolution … ‘gradual, subtle, exceedingly small and somewhat inchoate at first’—like the revolution of Christianity in its first centuries—’slowly introducing its vision of divine, cosmic, and human reality into the culture around it, often by deeds rather than words’… (175).

Within a single decade under the peculiar roof of St Menas’ Monastery in Old Cairo was to be found—almost without exception—every reforming voice of the Coptic Church in the twentieth century. It was, and this is no exaggeration, the embryo of reform, a ‘model for the new era’ (174).

And the most critical feature in the significance of this story is coming next…

it is the emptying

The self-emptying life of Jesus described in Philippians 2—for which the Greek work, kenosis, is often used—is Father Mina’s inspiration and aspiration. ‘Tis a little more than reminiscing this time! For him, this “self-emptying love was the one necessary means of healing the tensions of human existence, (be they) personal, ecclesial or national” (76).

To be honest, I battled to hear a crystal clear definition of what a ‘kenotic life’ is—but I did overhear it being lived in different ways. It is the life that does not exploit status; the life that lays aside personal rights in the selfless service of others and of God; the life that does not demand justice for oneself; the life that walks towards critics for the purpose of reconciliation; the life that sees the enemy as family (a family for which he is the father); the life that “always let others participate with him” (312); the life that may seek solitude, but can forsake it as well, for the sake of others; the life that mixes humility with courage; and the life, that when all is said done, is a ‘method of loss’, a ‘vocation of loss’.

This life reached a climax when Kyrillos was appointed patriarch. Initially, a group of ‘Sunday School monks’ were the candidates—but their youthfulness, among other things, caused too much controversy. The government steps in and stops the election. But eventually attention turns to their mentor as a possible candidate. Sure enough, through an altar ballot, in which a five year old boy reaches into a sealed envelope containing the various nomination papers, Father Mina was selected…!

I have always lived as a solitary, my God, and I would continue to live and die a solitary. But you have not wanted it. My God, may your will be done, for your will is impenetrable and you are mysterious, Lord (223).

Later at his ordination, “Kyrillos wept profusely and uncontrollably and would do so, with handkerchief in hand, for the rest of the Liturgy” (225).

But back to Philippians 2 for a moment. Let’s remember that the example of Jesus, in 2.5-11, isn’t even the main point of the passage. It is an illustration. The passage is about a conflicted and divided local church finding unity through living lives of humility (2.1-4). “Let this mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus” (2.5). True for the Philippians—and also true for the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Acutely aware of the need of unity for healing, Kyrillos was utterly convinced that this unity must be in a very real sense kenotic, that is, self-emptying. Each competing voice of reform … must, without compromise, ‘disappear’ that Christ may appear and heal his despondent Church (226).

At one point Father Daniel includes a little GK Chesterton—“it is the paradox of history that each generation is converted by the saint who contradicts it the most” (180)—and then he goes on to add these words:

Father Mina’s urban monasticism stands at the very center of this conversion in modern-day Egypt. The Church and society that was clamoring for modernism by way of revolution were healed by the one who most contradicted it—a monk providentially forced into the public eye; a monk who sought to be small, hidden, and unknown (180).

it is the opposition

It is hard to describe how tough things had become in the Coptic Orthodox Church by the time of the 1950s. The previous patriarch had been abducted and dethroned, having allowed a dubious character alongside him far too much power. You can feel the burden in the way Father Daniel structures the book: two weighty parts—A Hidden Life in God (21-194) and A Reluctant Patriarch (219-383)—is divided by a skinny Melancholic Interval.

The Church was in an inconsolable state of mourning (210).

It is hard to do justice to complex issues in a few short paragraphs, but I must try so that you can feel the impact of Kyrillos’ response. The opposition came in three ways: (a) from within the church; (b) from the wider society; and (c) from beyond the borders of Egypt.

Within the church… The maglis wanted the waqf. Simple, eh?! It is the classic battle between clergy and laity. For pretty much 100 years the maglis had controlled the Church—basically, an example of “the legitimization of laymen … over and against, so they claimed—incapable, incompetent, and relatively illiterate clergy” (196). But there’s more to it. The clergy/monasteries had massive amounts of money, kinda like endowments—the waqf. When Kyrillos became patriarch the maglis controlled the waqf and were misusing it. As a result, “parishes became desolate, sacraments were not administered, and the once faithful became disillusioned” (198).

The wider society… This is a Muslim context. So it easily becomes a situation that is ever so familiar for the vast majority of believers worldwide, even today: not just corruption from inside, but also persecution from outside. While the more extreme Muslim Brotherhood had been repressed by Nasser (only to go underground, ready to sprout again), he himself was no friend of the Coptic Orthodox Church. His Islamicisation of public life was carrying on at pace. His policies damaged the Church politically and economically. The departing Coptic diaspora becomes a flood and those that remain become “an alien population within their own land” (278).

Beyond the borders of Egypt… For centuries, it was the Coptic patriarchs who nominated and consecrated the head of the Ethiopian church. The Ethiopians, with Haile Selassie as Emperor, were saying, “No more. Enough.” It was heated and contentious.

I kinda gasped as I read how quickly and decisively Kyrillos VI steps into these oppositions. Let me move back through them, in reverse order.

A few days after he is enthroned, Kyrillos invites the Ethiopian Church to come to his ordination—he is “yearning, for the first time in history, that ‘they place their hands on his head’, and thus share in his consecration” (270). Nasser says, “No way”. Kyrillos persists. And in “barely six weeks … he heals the fractures” (271) of centuries by granting independence to the Ethiopian church. They may have been demanding it, but “it is Kyrillos who writes, initiates, compromises and makes their struggle his own” (271).

Can you see it?

Father Daniel is at pains to show us how Kyrillos’ personal kenosis is now becoming a ‘kenotic ecclesiology’—his way of doing church, if you like. Here, listen to these words:

What was imperative and vital for the Kingdom was done—and done immediately. It was a lucid moment of national and ethnic kenosis and self-emptying. It was the loss of ecclesial and patriarchal status, influence and authority; indeed, the loss of Ethiopia at the cost of his own Alexandria. The loss of a church for the Church (270-271).

Things are tense in the wider Muslim society in Egypt. The word ‘Crusades’ is on peoples’ lips. Muslims are killing Christians. So what does Kyrillos do—again, very early on? He becomes the first patriarch to visit the al-Azhar Mosque for a one-on-one with the grand imam, Sheikh Hassan Mamoun. Off he goes, leaving his patriarchal staff in the car and putting the cross he wore in his pocket. He enters the room and notices a Parkinsonian tremor in the elderly Sheikh’s hands.

Without a word, Kyrillos took and stilled the sheikh’s hand between his own hands. Touched by the love and gentleness of Kyrillos, Sheikh Mamoun’s heart was opened before his mind (274).

They have a little chat, with Kyrillos posing a question:

Permit me to ask you a question—’the Crusades, was it a war between the Christians and Muslims of Egypt, or between Western foreigners and Muslims?‘ (274).

‘It was undoubtedly’, replied Mamoun, ‘between foreigners and Muslims!‘ (274).

It is just so reminiscent of Jesus. A probing little question… It is uncanny. The very next day, out goes a declaration from the imam that stops the killing.

Kyrillos struggled to get a hearing with Nasser to discuss the treatment of the Copts. Eventually, it happens, but in a bit of ‘a shaking the dust off the feet’ moment Kyrillos actually walks out on the President. He is beckoned back later that same evening after Nasser’s daughter becomes ill—and we already know what happened.

‘From this moment,’ the president mumbled to the patriarch, ‘I will call you my father, and in the future, do not go to the presidential palace, but rather when you meet me, you meet me in my house. And these children … are like your children … pray for us in the same way exactly as you do for your family‘ (282).

… a period of deep animosity was abruptly and powerfully aborted by that meeting in October 1959 … (and) a deep, palpable and authentic friendship ensued suddenly that evening (282-283).

And what about the maglis and the waqf saga? “Kyrillos brought (it) to an end” (297)—and one of the things he did to address ‘the desolation and disillusionment’ among the people was to build a new monastery near Alexandria. Yes, you guessed it—consecrating the site within days of becoming patriarch (and with it being named after St Menas, of course!). The idea of pilgrimage, so critical in his own childhood, was revived—and in doing so, it “rehabilitated Coptic identity … laying the foundation stone of reform” (254).

After all is said and done, these are classic case studies on managing conflict and change—and by a man who hardly says a word. But in it all, ‘holiness begets holiness’ as “reform springs, again and again, from his self-emptying” (350)—which is where we now turn.

it is the reformation

We need not linger at this destination because we have been glimpsing it right through this journey. “Ever aware of the need for his own transformation as a precondition of the transformation of the Church” (225)—Kyrillos proceeds to “steer the ship of this Church to its harbor of salvation” (270).

You can read more about it for yourself—but I think the Canadian Copt by the Cave (and Father Daniel himself, given the amount of pages he devotes to it!) would want me to pause in one more ‘rest area’. Once again, so reminiscent of Jesus is the way Kyrillos draws those Sunday School monks/disciples into leadership roles. He can’t afford to wait around for bishops to ‘repose’ to effect change. So he comes up with this plan to appoint ‘general bishops’ with functional roles rather than geographical parishes. These functions, or portfolios, are: (a) seminary education; (b) public and social affairs; (c) diaspora; and (d) liturgical rites. One of the four—”the least obedient” (335)—is more widely known now as Matthew the Poor, while another succeeded Kyrillos as patriarch and served for 40 years (Shenouda III)!

The four of them are unevenly sanctified, drawn into conflicts and tension (even with Kyrillos himself)—but then in “unsuspecting” ways, even on rather spontaneous occasions, Kyrillos “forces” them into ordination. In one of them he saw “something seemingly worthy of perpetual forgiveness” (344). Isn’t that beautiful? I wanna be like that when I grow up.

It took me back to the earlier story that launches this section about these general bishops—and to another two pages that need to be read aloud (pages 307-308). It is about Kyrillos’ handling of a corrupt priest. He brought him to be with him for six months, in the face of severe criticism:

It was not the reputation of the priest that concerned him, but rather healing him. Kyrillos refused to turn a blind eye to the corruption, but neither was he willing to forsake the corrupt priest.

This episode was paradigmatic of Kyrillos’ method of reform: always at a cost to himself; through his personal holiness and ascetic influence; and, above all, quietly, without judgement, seeking only healing … Just as he healed the priest, Kyrillos took into his bosom a broken, fractured and impoverished Church, silently bearing all manner of ridicule, gently healing with his person. This would be characteristic of his ‘method’ of reform (308).

A personal life of kenosis, as Christ is formed in him—and then this kenotic leadership and ecclesiology.

The author, Rev Dr Daniel Fanous, is Dean at St Cyril’s Coptic Orthodox Theological College in Sydney. On a visit last month I was unsuccessful in making contact with him, but I am going to keep trying because I’d love to thank him in-person for this book.

Sometimes I ask myself, “Paul, why do you wake up so early on weekends to write these long ponderous posts which, let’s face it, not that many people are going to read?” The return on investment, as they say, is average, at best. One response is ever before me. When faced with stories like this one—and I’d put last year’s Bishop Azariah story in a similar category—something comes over me. Becoming obsessed mingles with being overwhelmed. There is this compulsion to listen, to learn and to honour—and a desperation that others be doing so as well. I am in awe of a Church that has maintained a witness to Christ from the very beginning, even through the Islamic onslaught which almost eliminated the Christian presence in its Middle Eastern homelands. And as we consider mission in our own countries—especially in ‘the West’—we should quit being such chronological and cultural snobs, and sit attentively at the feet of the ancient and the distant. It will help us be a bit more reminiscent of Jesus as well. And in this wired and connected world of ours, we are without excuse.

nice chatting

Paul

PS: Let’s remember that ‘lest we forget’ applies to world wars—and more…

About Me

the art of unpacking

After a childhood in India, a theological training in the USA and a pastoral ministry in Southland (New Zealand), I spent twenty years in theological education in New Zealand — first at Laidlaw College and then at Carey Baptist College, where I served as principal. In 2009 I began working with Langham Partnership and since 2013 I have been the Programme Director (Langham Preaching). Through it all I've cherished the experience of the 'gracious hand of God upon me' and I've relished the opportunity to 'unpack', or exegete, all that I encounter in my walk through life with Jesus.

6 Comments

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Football helps me train preachers. See, when you speak to me about football—or, ‘footie’—I need to know where your feet are before I can understand what you mean. Are your feet in Ireland, or Brazil, or the USA, or NZ—or in crazy Australia? It must be the most fanatical sporting nation in the world. Within…

Having been born in 1959, I don’t remember much about the 1960s. But I have heard a lot. Hippies. Drugs. Rock ‘n Roll. Assassinations. Moon-walking. A quick trip across to ChatGPT informs me immediately that it was ‘a transformative decade across the world’—marked by the civil rights and feminist movements, Cold War tensions, consumerism and…

Paul, WOW! This is an amazing review of the book. Great lessons for church and its mission in a complex world. Story of Nasser’s daughter healing and its outcome is wonderful. By the way, in one of my explorations I found that Habib Gerges has written exceptional hymns that even evangelical churches sing in their worship services. And thank you for your last comment ‘to listen, to learn and to honor.’

Thank-you, Riad. So many beautiful stories — and I think the itinerary for my next visit to Egypt has just become much longer :).

You’ll need to introduce me to some of those hymns when I visit you in Lebanon later this year.

Thanks Paul for recommending the book too me a few weeks ago. I also found it fascinating and inspiring, a wonderful human being and leader whom God used extraordinarily. Thanks for your reflections. And I want to join you and Riad in signing these hymns!! I wish I had read this book before I visited monasteries in Wadi Al-Natrun.

So good, Paul — and I suspect you’ll meet the author before I do. Give him my greetings and thanks :).

I have a little itinerary, getting longer with each passing book, for the next time in Egypt.

best wishes

Thanks for reminding me of this Paul. Our dear friend Flemming ran to over 600 pages and now you are offering me another brick! I wrote to someone recently (an author of a hugely significant book that I want you to read!) that at the age of 70 I am becoming very very selective re the books I choose to read – no time for duds! But I have the feeling this one is going to be worthwhile! Am encouraged that his work as pope took place at the end of life and within about a decade!!!

Love the catechetical too. In a small way that’s what our little church is about to embark upon. I remember another brick – in fact two bricks – on the life of MLJ. When he got to Westminster he decerned that his people were not regenerate – really had never been faced with the need – merely products of Christendom. Anyhow he did nothing, just started catechising them through Sunday sermons and mid week Bible studies. After a while it became evident that the great majority of his congregation had a living experience of Jesus!

And thanks for your personal word Paul. The reminder that – “a conflicted and divided church finds unity through living lives of humility.” Powerful! True for the Philippians – and also true for the Coptic Orthodox Church… and also true for _________ (fill in the b lank) 🙂

Sorry about this – but I can’t help but comment on your comments! Wow! How this applies to the contemporary church scene… “The church and society that was clamouring for modernism… were healed by the one who most contradicted it.”! That’s one in the eye for relevance!

Well – thou persuadest me… I’m jumping on Amazon to buy the book. And thanks Paul for waking up so early on the weekends to write….

Yes, Father Fred

I think this is a story you’d enjoy, especially with your penchant for ‘smells and bells’ worship and liturgy 🙂

Let me know how you get on

Paul