With this post I return to Lamin Sanneh’s autobiography, Summoned from the Margin, for a third reflection (also, see here and here) on his life story. I really wanted to write this post when in Melanesia last week, but I just could not get there, as life was too full.

Many years ago, it was Sanneh who helped me see that everything God wants to say to a people – yes, even every single people group in Melanesia – he can say to them in their own heart language. God’s commitment to the vernacular is spectacular. It has become one of the central reasons why I am a Christian.

We talk about incarnation as God becoming a human being, but what about this other incarnation? The word of God coming in the words of human beings – yes, even every one of their vernacular languages. I loved the way this book gave me the opportunity to watch Sanneh’s life story move towards this conclusion, with its various implications. Can I take you on this journey with me? It may take a little time, but as it is one of the most stunning discoveries for me over the last few decades, I’d like to savour his story. Listen to how Sanneh expresses it as he reflects back on the journey:

I came to this subject reluctantly and incredulously … it collides with too many announced positions; it transgresses too many norms of career self-interest; it calls into question too many certainties of the guild; and it flies in the face of too many deeply entrenched canons of decolonization and its nationalist allies for it to be a career path for anyone (226).

The story begins in his homeland of The Gambia, as a Muslim lad in a Qur’an school.

Knowing that the mother tongue was not fit for faith and worship, we had no esteem for the vernacular … Even the little we understood made us realise that Arabic was special: that the words had a holy reputation and a sacred personality; that they never changed or aged; that we suffered for offending against them, for soiling them, and for tripping over them … Surely, the walls of God’s truth would not tumble because the untrained tongue got involved, I would muse aimlessly (39, 40).

The transition to secondary school deepened his questions, ‘enhanced by the demands of competing languages’ (67) in his education: English, Arabic – but with his mother tongue, despite its inferiority, remaining in his heart:

From the religious point of view, it is not difficult to establish mother tongue inferiority. The language took root nowhere outside the walls of those who spoke it; it had no written literature to advertise and promote it; no orthography for written communication; no forum of shared ideas; and no organized, institutional means of transmitting knowledge beyond the oral medium … To be religious required listening to God in the revealed language (ie Arabic), and that demoted the mother tongue to the religious black market … It is not possible to conceive a divine role for the vernacular against the transcendent Arabic, thus making worship a ban on the mother tongue. My own language was at best mundane and vain. I could plead and pour out my soul before God but it would be without the merit of worship. In the tones and sounds I learned from my mother, lively thoughts of God formed in my mind, only to dissipate with the worship. To make matters worse, the school instituted English, and placed a ban on the vernacular … The language of school and the language of worship together tied my tongue up. But it was hard to turn my back on the language my mother had taught me (67-68).

Did you hear that observation? ‘The language of school and the language of worship together tied my tongue up. But it was hard to turn my back on the language my mother had taught me’. WOW. By now Sanneh was heading for some serious trouble, especially with his ‘inquisitive and skeptical’ leanings. His mind was opening up to another world, with the classic novels of English literature influencing his education, just as ‘a chance encounter’ with the writings of Helen Keller at eight years of age – ‘I was walking down a dirt road and I kicked up a pile of papers strewn at a garbage dump’ (17) – had influenced his spiritual longings. It turned out to be remnants of Helen Keller’s autobiography. While ‘more than a thousand years of Islamization had contributed to making Christianity virtually invisible to us’ (19), God had begun to break through to him, as a little lad, in the spiritual journey of Helen Keller.

Let’s pick up the story at a much later vantage point. Sanneh is transitioning from Aberdeen to Harvard, becoming a professor of World Christianity and being asked to teach a course on African Christianity, a task which sparked little enthusiasm within him, initially. However ‘I found myself stumped by a nagging problem in the sources for which I was totally unprepared’ (216). Like all of us, Sanneh had been trained to think of ‘Christian missions as Western cultural imposition only’ (216-217). But now a ‘thought sat like an undigested lump in my throat’ (216). Here is what ‘stumped’ him:

… the apparent facility with which Western missions downloaded the text of scripture into the vernacular idiom, adopting in the process the local concept of God. We are taught that pagan gods seep with all that is scandalous and unredeemable about polytheist religions and yet here are missionaries, who ought to know better, embracing them with equanimity. Gales swept through my mind and left me speechless. It stumped me that, in spite of its relative disadvantage as an undocumented language without any literary works to its credit, the mother tongue should attract the interest and devotion of missionaries who made it the language of scripture – something Muslim agents would never dream of doing … The more I read, the more deeply I seemed to sink into the vernacular footprints of missionary agents, and the more restless I became with conventional views (216-217).

Dare he challenge ‘the tempered judgement of historians’? Should their views not ‘prevail over my fledgling instincts?’ Thankfully, ‘instinct defied caution, and a beginner’s energy shoved aside the the set habits of old practice’ (217). He jumped in and drew the conclusion that the data demanded from him:

Angels fear to tread on the ground that seemed absolutely irresistible to the beginner: Christianity is a form of indigenous empowerment by virtue of vernacular translation (emphasis his), it was becoming clear to me. Ethnic self-preservation, it turns out, has a champion in missionary translation projects (217).

“Yikes?! Did you just say that, as a child of West Africa in colonial times? Surely not.” Yes, he did say it. We need to recalibrate that stuff we hear about ‘Christian mission as willful cultural imperialism’ (223). It ain’t necessarily so. Sure, some missionaries were ‘bad eggs’, but I suspect a fair few secular anthropologists were as well. In light of Sanneh’s contribution (field-tested within the Harvard faculty, remember!), it is no longer reasonable to assert, so sweepingly, that missionaries ruined culture. As John Watters writes, in his tribute to Lamin Sanneh earlier this year, rather than Western missions being a form of cultural imperialism, it actually ‘pursued a form of cultural affirmation’.

For Sanneh, whereas the Qur’an was ‘nontranslatable’ (217 – there are translations, of course, but such translations have ‘no canonical status’ (224)), he was now face-to-face with a Christianity that was so different:

I noted to my colleagues my surprise that Christianity seems unique in being a missionary religion that is transmitted without the language of the founder of the religion and, furthermore, how the religion invests itself in all languages except the language of Jesus. It is as if the religion must disown the language of Jesus to be the faith Jesus taught. Christians do not pray, worship, or perform their devotions in the language of Jesus (222).

What an observation! ‘It is as if the religion must disown the language of Jesus to be the faith Jesus taught.’ It is similar to the one that CS Lewis makes in God in the Dock (230): ‘The same divine humility which decreed that God should become a baby at a peasant-woman’s breast, and later an arrested field-preacher in the hands of the Roman police, decreed also that He should be preached in a vulgar, prosaic and unliterary language’.

For Sanneh, there are consequences to God’s commitment to the languages of common people:

Christians came upon language not as an obstacle, but as an asset in its own right. It led to systematic, rigorous documentation of the world’s languages, without which cultures remain marginal and remote … Without the specific, earthy embodiment of language, Christians would not know themselves or their God.

The most tangible expressions of this vernacular impulse are the orthographies, grammars, dictionaries, and other linguistic tools the Western missionary movement created to constitute the most detailed, systematic, and extensive cultural stocktaking of the world’s languages ever undertaken (225).

Eventually, Sanneh’s thesis appeared in Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact of Culture. It has gone through 17 printings, before being revised and expanded. Remarkable. One of his main affirmations in the book is that the earlier, much earlier, Western Christianity is itself the fruit of this same commitment to vernacular translations that we see happening more recently in post-Western Christianity. How else do you think the celebrated art, music and architecture of European Christianity could be born in the first place?

This leads on to a further question. If Western missions had been so tied to colonialism, should not the end of colonial rule ‘set in motion the demise of Christianity’? (228). That is a reasonable assumption to make. And yet we know that the exact opposite has been true, as there has been this ‘crush of new converts … in the very areas where colonial rule was supposed to have turned people against the (Christian) religion’ (229). At the roots of this awakening is something ‘vernacular, rural, young and largely illiterate or semi-literate’ (233) – the very setting where the gospel is so adept at making a home and having an influence for good.

Vernacular transltion is the key to cultural retrieval, renewal and transformation, the secret to intercultural encounter in its positive phase. Without translation and its indigenous currency, cultural symbols in their isolation atrophy and eventually disappear when challenged (233).

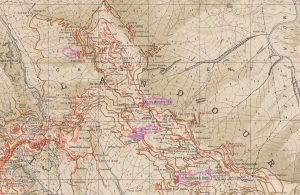

The global church has some catching up to do here. ‘The physical map of Christianity looks very different from the mental map of the religion’ (231) – by which he means that people are still locating the intellectual centre of Christianity to be in Europe and North America, even as the overwhelming weight and influence of the faith has moved on to other parts of the world. This is why developing a body of scholarship and literature in this Majority World is so urgent and critical.

It is to this ‘post-Western resurgence’ (229) that Sanneh next travelled, as captured in his Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity. The colonial powers are long gone and Christianity’s spread can not be linked to their coercive power, but to the power of the gospel, with its own compelling truth claims, as it becomes embedded in local cultures, sparked by translation into vernacular languages.

nice chatting

Paul

About Me

the art of unpacking

After a childhood in India, a theological training in the USA and a pastoral ministry in Southland (New Zealand), I spent twenty years in theological education in New Zealand — first at Laidlaw College and then at Carey Baptist College, where I served as principal. In 2009 I began working with Langham Partnership and since 2013 I have been the Programme Director (Langham Preaching). Through it all I've cherished the experience of the 'gracious hand of God upon me' and I've relished the opportunity to 'unpack', or exegete, all that I encounter in my walk through life with Jesus.

7 Comments

Leave a Comment

Recent Posts

Football helps me train preachers. See, when you speak to me about football—or, ‘footie’—I need to know where your feet are before I can understand what you mean. Are your feet in Ireland, or Brazil, or the USA, or NZ—or in crazy Australia? It must be the most fanatical sporting nation in the world. Within…

Having been born in 1959, I don’t remember much about the 1960s. But I have heard a lot. Hippies. Drugs. Rock ‘n Roll. Assassinations. Moon-walking. A quick trip across to ChatGPT informs me immediately that it was ‘a transformative decade across the world’—marked by the civil rights and feminist movements, Cold War tensions, consumerism and…

Oh Wow. SO loving the way this challenges the dualistic "imperialistic/colonialist/Missionary = Bad" verses "pure indigenous culture without the taint of Christianity = good" thinking that most of my English degree taught me.

Timely because last week Kiri was finishing off a research project on Samuel Marsden and came across a cartoon online which displayed Marsden as beating a maori (who was tied to a post) as part of bringing his Christain message. Confused 11 year old Kiri asks me if that really happened because previously she thought well of him. Explaining the nature of political cartoons was tricky, but I tried. She had obviously been chewing on it and came to the conclusion a few days later that 'a good missionary (I think 'good' meant 'effective') would not force his beliefs on anyone, but would get to know the person, their culture and listen to them and then share about God'. Time to for me to re-read your post again and translate it to 11 year old language in case of further conversations….

All the best with that translation, Hannah – and it sounds like Kiri is thriving :).

And yes, that dualism about which you speak does need to be challenged with a more nuanced engagement with missions and missionaries in the past. Sanneh's stuff is one way forward – and it helps that he was raised in West Africa.

Much love to each one of you

Paul

Thanks Paul – I'm inspired by the pattern of God's action; something like burning off a field for fresh grass to grow, destroying a Temple so that God's presence can be known everywhere, accepting discipline in order to grow, the Aramaic tongue Jesus employed becoming virtually crucified whilst the words He spoke live and thrive on myriad resurrection tongues. I am challenged as well to do a better job at everyday translation. I am reminded of the slogan: know the gospel, know the culture, translate.

Good Stuff. You've just given me my next Pentecost sermon!

So true, Dale. And Aotearoa-New Zealand is such a great place to explore these realities, with the prominence which Te Reo receives, increasingly. It is great to see.

Yes, Fred. You may be hatching ideas for your next Pentecost sermon, but I am also hatching ideas for our next collaboration around your art and my training of preachers! We need to talk :).

Happy to oblige… as they say in my favorite movie "Sure, I'll do anything for my godfather" (Of course I wouldn't dare to recommend my favorite movie, let along tell you what to think of it!!!)